By Deanna Belknap

Assistant Criminal District Attorney in Tarrant County

As a Texas prosecutor, I look forward to this journal landing on my desk. There’s something luxurious about taking a few moments out of a busy day to check out what other prosecutors around the state are doing. Having served on TDCAA’s Editorial Committee (which oversees the production of the journal) for three years, I have witnessed the amount of thought and effort that goes into every article to ensure it is relevant and appealing to TDCAA’S service group. I have been a prosecutor for about 11 years now and have managed Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) caseloads for roughly half that time.

Having both criminal and DFPS prosecution experience, plus insight into the workings of the editorial committee, I am in the fortunate position of writing an article or two for fellow DFPS prosecutors that I hope will also appeal to criminal prosecutors. I think those who will find this article most interesting are new child protection prosecutors, prosecutors in other divisions who are unfamiliar with yet interested in what their child protection colleagues do every day, and experienced prosecutors who have some interest in handling a DFPS caseload but would first like to know a little more about the cases.

A day in the life

I know from experience that even seasoned prosecutors face a pretty steep learning curve when shifting to a DFPS caseload. Trial skills are transferable, of course—child protection prosecutors are frequently in court. Knowledge of criminal prosecution processes, timelines, and lingo will also come in very handy as many of the parents in these cases have past and pending relevant criminal cases. But you are no longer working under the Code of Criminal Procedure and Penal Code—child protection prosecutors must learn family law and civil procedure! And you are not dealing with just one party (the defendant). It isn’t unusual to have a mom and two or three dads in a case, each entitled to representation, along with the child’s attorney ad litem and guardian ad litem. There is a great deal of interfacing with the local bar while maneuvering through the life of a DFPS case.

On any given day, a child protection prosecutor may be fielding emergency emails and phone calls from caseworkers on current cases, advising child protection investigators on emergency removals in new cases, presenting new removals to the court within a couple of hours of notice, appearing in court for scheduled statutory review hearings, prepping and appearing for contested trials and hearings, participating in mediations, and generally trying to keep up with daily case management tasks. It can be a challenging position because there are children’s safety issues arising daily that demand our attention—all while managing a planned calendar and ensuring you are not missing any critical deadlines.

Who represents DFPS

The governing statute for representation of DFPS in Texas family courts is found in the Family Code, which says the county attorney shall represent DFPS but the district attorney has the right of first refusal.[1] In some smaller counties, neither the CA nor the DA provides representation, but instead DFPS-employed regional attorneys manage the caseloads (DFPS has divided the state into 11 regions).[2] DFPS also has statutory authority to contract with private attorneys to handle its cases as long as the Attorney General approves.[3] In counties with a population of 2.8 million or more, the caseload must be carried by the county or district attorney’s office.[4] Just based on experience, it does appear the majority of Texas counties have dedicated prosecutors from either its county or district attorney’s offices managing these cases.

Practice Tip: If you need copies of DFPS’ records for one of your criminal cases, contact DFPS at www.dfps.texas/gov/policies/Case_Records/professional_duties.asp.

The two DFPS divisions child protection prosecutors work with are Child Protective Investigations (CPI) and Child Protective Services (CPS).[5] CPI manages child abuse and neglect cases during the investigative stage, while CPS manages the conservatorship stage of the case after legal removal of the child from the home. CPI and CPS were not always separate divisions; the investigation and conservatorship functions used to both be a part of the CPS program until a few years ago. Regardless of the recent division, some counties still use the old-school term, CPS prosecutors, to refer to those of us who handle child protection cases. Some counties refer to us as DFPS prosecutors (as CPI and CPS both fall under this department), while some counties may say child protection prosecutors. There is no right or wrong here, merely preference, and I will use the term “child protection prosecutors” in this article.

Child protection prosecutors and DFPS maintain an attorney-client relationship; the same privileges apply to their communications as in any attorney-client relationship. Although the child protection prosecutor may be privy to confidential information maintained by DFPS, the prosecutor’s office does not own DFPS’s records, just like a private attorney does not own the records of its corporate client. DFPS records are subject to many confidentiality laws pertaining to release, and a prosecutor does not have the authority to circumvent these laws.

By the numbers

During DFPS’s 2022 Fiscal Year (September 1, 2021–August 31, 2022), there were 310,848 allegations of child abuse or neglect made to CPI. Out of those allegations, CPI conducted 166,187 investigations. Out of those investigations, CPI made the following dispositions:

• Reason to Believe (RTB): 37,081

• Ruled Out (RO): 109,768

• Unable to Complete (UTC): 1,858

• Unable to Determine (UTD): 17,480

(Sidebar: DFPS is the king of acronyms. The department has acronyms for people, departments, stages of the case, service providers, types of foster homes, and on and on. If you are new to this world, just know it gets easier with time and cheat sheets are recommended!)

RTBs confirm abuse or neglect by a preponderance of the evidence; ROs confirm that abuse or neglect did not occur by a preponderance of the evidence; UTC means a determination could not be made because of an inability to gather enough facts; and UTD means neither an RTB nor an RO could be confirmed by a preponderance of the evidence. Out of the 37,081 cases where a preponderance of the evidence resulted in an RTB, 5,271 investigations resulted in legal removals. This can be translated to about 5,000 parental rights termination cases being filed in Texas family courts during DFPS’s 2022 Fiscal Year.[6] Let’s look at how that translates to four Texas counties—two small and two large, from two different DFPS regions:

This tiny snapshot gives some insight into how few allegations result in the legal removal of a child from the home. DFPS goes through great pains to prevent taking custody of children; there are numerous programs and efforts initiated by CPI to keep families together. The result is that it really is just the worst of the worst cases of child abuse and neglect that end up being filed by child protection prosecutors.

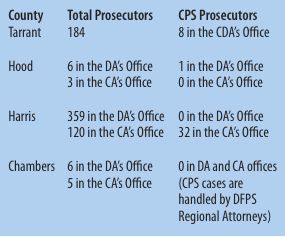

So, who are the Texas prosecutors stepping up to handle these child abuse and neglect cases? I have discovered there is no simple way to tally how many child protection prosecutors there are in Texas. Below are some stats about how few such prosecutors there are compared to criminal prosecutors, referencing the same counties as in the previous table:[7]

Types of DFPS suits related to the safety of children

There are a handful of civil suits DFPS has the authority to file. Counties may handle all or some of these suits, depending on their agreement with DFPS. The following four actions may be implemented to prevent the legal removal of a child from the home:

Petition for Orders in Aid of Investigation:[8] This suit is filed against a parent who is interfering with DFPS’s right to effectively investigate allegations of abuse or neglect. The relief is a court order that may include giving DFPS access to a child’s school or shelter, access to a child’s medical records, and the right to have a child examined by a medical doctor, including drug testing and psychological exams.

Petition for Court Ordered Services:[9] This suit is filed against a non-compliant parent to whom DFPS is offering services to alleviate the effects of abuse or neglect that has already occurred, to reduce the continuing danger to the health and safety of a child, or to reduce the risk of abuse or neglect to a child. The goal in these cases is to prevent legal removal of the child while requiring the parent to engage in tailored services to assist in being a safer parent, such as drug and alcohol education and mental health assessments and appointments.

Protective Orders:[10] Protective orders can be useful tools to protect a child from being a victim of domestic violence in the home or witnessing domestic violence between parents in the home. A protective order may address many issues that, if left unresolved, could lead to the legal removal of a child from the home.

Petition for Removal of Alleged Perpetrator:[11] Much like a protective order, this kick-out order can be an effective means of protecting a child from an abuser if the removal of the abuser from the home is all that is necessary to protect the child. This situation requires the caregiver in the home to be protective and report any attempt by the perpetrator to return to the residence.

Termination of parental rights cases

The Child Protection Suit is a suit affecting the parent child relationship (SAPCR) that is filed by DFPS when a child is legally removed from the home. These suits are governed by Chapter 262 of the Family Code (Suit by Governmental Agency to Protect Child); they are initiated by filing the Original Petition for Protection of a Child (OP); and they often end with a final trial terminating parental rights.

Termination of Parental Rights cases run on strict statutory timelines. For prosecutors interested in learning about the life of a child protection case, here is a timeline and summary of the hearings that drive these cases, sprinkled with a few practice tips and anecdotes.

Day 1: Removal. Once CPI exhausts its efforts to prevent the removal of a child from the home, it submits a request to the prosecutor to start the legal process that allows DFPS to keep or take emergency custody of the child. The prosecutor must review the facts of the removal and address any questions and concerns with the investigator. The petition and its supporting affidavit have to be drafted and filed, and an appearance must be made in front of the court. Removal requests come up unplanned and immediate, and the process moves extremely fast. Typically, it all takes place the same day—within a couple of hours. Removals aren’t picky, either: They happen on your busiest days and your catch-up days. As child protection prosecutors, we have to be able to shift gears as soon as we hear the words, “We just got a removal.” Sometimes there is more than one in a day!

Without a court order. When DFPS takes possession of a child without a court order, because there isn’t enough time consistent with the health and safety of the child to get in front of the court, you have one business day to file the OP and request emergency relief from the court, or by law CPI must return the child home.

The burden CPI must meet to keep emergency custody of a child it has taken into its possession without a court order is sufficient facts to satisfy a person of ordinary prudence and caution that:

• there was an immediate danger to the physical health or safety of the child;

• the child was the victim of sexual abuse or trafficking;

• the parent or person who had possession of the child was using a controlled substance and the use constituted an immediate danger to the physical health or safety of the child; or

• the parent or person who had possession of the child permitted the child to remain on premises used for the manufacture of methamphetamine; and

* continuation of the child in the home would have been contrary to the child’s welfare;

* there was no time consistent with the physical health or safety of the child for a full adversary hearing; and

* reasonable efforts consistent with the circumstances and providing for the safety of the child were made to prevent or eliminate the need for the removal of the child.[12]

Practice Tip: Make sure you know a few really seasoned child protection prosecutors that you can text on short notice for advice on how to handle last minute surprises in court.

With a court order. When there is time consistent with the health and safety of the child to file an OP, a child protection prosecutor will appear before the court the same day to request an emergency order, which then allows CPI to remove the child from the home.

The burden CPI must meet to take custody of a child with a court order is sufficient facts to satisfy a person of ordinary prudence and caution that:

• there is an immediate danger to the physical health or safety of the child or the child has been a victim of neglect or sexual abuse;

• continuation in the home would be contrary to the child’s welfare;

• there is no time, consistent with the physical health or safety of the child, for a full adversary hearing; and

• reasonable efforts, consistent with the circumstances and providing for the safety of the child, were made to prevent or eliminate the need for the removal of the child.[13]

Whether it’s a removal with or without a court order, this initial hearing is an ex parte proceeding between DFPS and the court. If the court determines DFPS should keep or take emergency custody of a child, it will grant an emergency protective order (EPO) setting the case for an Adversary Hearing within 14 days. Parents must be notified of the removal and the Adversary Hearing. When DFPS takes emergency custody, the child is placed outside of the home with family or fictive kin if appropriate; if not, then into the foster care system he goes. (Fictive kin are not legally related to the child, but these are people with whom the child has an emotionally significant relationship—family friends, baby-sitters, school staff, etc.)

If upon review we determine a request for removal doesn’t meet the legal burden, as the prosecutor, you have a choice. You can simply deny the request, drink your coffee while it’s still hot, and carry on with your planned day. Or you can stop what you are doing and immediately contact the investigator to dig deeper into the investigation. A lot of times I find that the burden really is met, but that the investigator just needs some guidance on which facts are relevant to the removal and how to best articulate those facts in their affidavit. Practice Tip: Create a template removal affidavit form with sections for each topic that must be addressed by CPI in the removal. For example, we are adding a Reasonable Efforts section based on the new requirement coming out of the 88th Legislative Session that the affidavit must describe all reasonable efforts made to prevent or eliminate the need for the removal of the child.[14]

Day 14: Adversary Hearing. This is when a parent can challenge the legality of the removal and when DFPS asks the court to upgrade its emergency possession status to temporary managing conservatorship (TMC) of the child. You can imagine parents are pretty hot, as their child has been physically removed and placed outside of their custody for a couple of weeks by now. As this hearing occurs pretty fast after removal, it can really test a prosecutor’s ability to pull evidence together quickly. There is no exception to the application of the Texas Rules of Evidence—the rules apply, short notice or not. And these hearings often look like full-blown final trials with subpoenaed witnesses such as schoolteachers, police officers, family members, and custodians of record.

The burden at this hearing is sufficient evidence to satisfy a person of ordinary prudence and caution that:

• there is a continuing danger to the physical health or safety of the child caused by an act or failure to act of the person entitled to possession of the child, and continuation of the child in the home would be contrary to the child’s welfare; and

• reasonable efforts, consistent with the circumstances and providing for the safety of the child, were made to prevent or eliminate the need for the removal of the child.[15]

If DFPS does not meet this burden, the child is returned home. If DFPS does meet its burden, DFPS maintains temporary custody while it works with the family to reunify the child with the parents.[16] I am personally surprised by how many parents agree to give DFPS temporary custody of their children at this stage. I mean seriously: The State has taken your kids and you have a court-appointed attorney—what have you got to lose by fighting DFPS? Regardless, we get a lot of agreed temporary orders. Certain cases are almost always contested at this early stage, though, and those are the “broken baby” cases—physical abuse cases of infants where one or both parents are under criminal investigation for child abuse.

Day 60: Status Hearing. At this hearing, the court is required to review two issues: 1) the status of service of the lawsuit on the parties, and 2) the “service plan” developed for the family.

Executing service can get tricky and must be in strict compliance with the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure; the failure to properly serve a parent or alleged parent can delay resolution or open a door to a credible appellate complaint. There are rules for serving legal parents, missing parents, unknown fathers, and alleged fathers. Even when you think you have everyone properly served, there are still surprises. I once had a caseworker make one last attempt to contact a missing father on the eve of trial—in her mind this was necessary to testify to the fact she had made diligent efforts to find him—and he answered her call at a number that hadn’t worked throughout the entire case! Relevance, you ask? We now have located an alleged father who is entitled to notice that we have not personally served. There are procedural ways to handle these surprises, but you have to be careful not to jeopardize a case by extending beyond its deadlines.

Practice Tip: If a parent refuses to sign a temporary order at this stage because there are criminal charges pending or possible, refer his or her counsel to §262.013 of the Family Code, which says a parent’s agreement to give DFPS temporary custody of their child is not an admission that they engaged in conduct that endangered the child. I’ve always been curious if criminal prosecutors see Motions in Limine to keep out agreed temporary orders from child protection cases. It seems like this little statute isn’t well known but could be pretty favorable to a parent facing criminal charges.

The Service Plan is governed by Chapter 263, Subchapter B of the Family Code. It must be filed by DFPS no later than 45 days from the date the temporary order is granted.[17] It is the plan of action created by DFPS, with the parents’ input, that will (we hope) rehabilitate the parents and allow them to become safe parents. Failure to comply with a court-ordered service plan is a ground for termination,[18] but with a parent’s commitment, it is the vehicle that results in the return of their children. Service plans must be tailored to each family’s circumstances and needs; common services included in these plans are drug and alcohol assessments and treatment, psychological assessments and mental health treatment, individual counseling, domestic violence counseling, family therapy, and requirements of housing and employment stability. DFPS has the burden of making reasonable efforts to reunify the family; and creating a tailored, effective, workable service plan is part of this requirement. In my experience, this isn’t always easy. For example, finding a Spanish speaking domestic violence counselor who accepts payment from the State can be nearly impossible. If DFPS can find one, the wait list to get in is longer than the life of the case. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen caseworkers report that a parent has not complied with a service plan only to find out later that the reason for the non-compliance is DFPS’s inability to locate a provider.

There are a few “aggravated circumstances,” when, if approved by the court, DFPS is not required to create a service plan or make reasonable efforts to reunify the family.[19] A few examples of aggravated circumstances include a parent who abandoned a child without any means for identification, a parent who inflicted serious bodily injury or sexual abuse on a child, and a parent who engaged in criminal conduct against the child, such as possession of child pornography or trafficking. In these cases, you can set your final trial pretty quick, terminate parental rights, and, let’s hope, progress the child towards permanency in a safe, loving home.

Practice Tip: As the prosecutor, make sure you understand these nuances before the review hearings so you can guide your client (DFPS) to what is “reasonable” with respect to service plan requirements. You don’t want this testimony to unfold in front of the judge because DFPS will lose its credibility.

Day 180: Initial Permanency Hearing. This hearing is when the court reviews DFPS’s permanency goal for the child to ensure that the case is on track for a timely, final resolution. By this time, DFPS should be ready to announce whether it is moving for parental termination or if there is another goal, such as family reunification or conservatorship to a relative. The court also reviews the appropriateness of the child’s placement; whether the child’s physical, medical, and emotional needs are being met; and the compliance of the parents with their service plans.[20]

Practice Tip: Some counties require mediation while others do not. Regardless, once your permanency goal is established, a case should be ripening for mediation. Mediation can be especially beneficial in cases where all you really have left are custody arguments and not safety concerns. So, if a case is starting to look like a custody battle instead of a child protection case, set it for mediation.

Day 300: Second Permanency Hearing. After the Initial Permanency Hearing, and before the final trial, the court must hold an additional permanency hearing every 120 days. Cases finalizing within one year will have only two permanency hearings, but cases in extended timelines may have another one or two permanency hearings before final resolution of the case.

After Day 270 and Before Day 365: Final Trial. DFPS prosecutors must ensure proper procedures are in place so their final trials are heard before the one-year mandatory dismissal date. Case management is so incredibly important. If a case hits that drop-dead date and the parties haven’t requested and received an extension order, the case gets dismissed and the legal status of the child returns to what it was before DFPS took temporary custody. Simply put, the child goes home, and that’s every child protection prosecutor’s fear.

As with criminal cases, CPS trials can be jury or bench trials. These cases are often hotly contested and involve multiple parties. As stated earlier, parents and children have the right to be represented by attorneys, and indigent parents are entitled to court-appointed attorneys. So it’s not unusual to have a pretty full courtroom with four or more represented parties at a final trial.

The burden to terminate parental rights is clear and convincing evidence. The State must prove at least one statutory ground for termination. There are several grounds, and one of the most common sought is that the parent has “engaged in conduct or knowingly placed the child with persons who engaged in conduct, which endangered the physical or emotional well-being of the child.”[21] In addition, DFPS must prove that termination is in the child’s best interest. Sometimes this best interest piece is actually the harder point to prove. For example, if a child is having severe behavioral issues in care and is bouncing from placement to placement, adoption may not be a realistic outcome for that child. So instead of severing the parent child relationship, would it be better for the child if DFPS took permanent custody without terminating parental rights in the hopes the parents are able to rehabilitate themselves down the road?

In termination cases, DFPS is named as the child’s permanent managing conservator (PMC), and the State essentially becomes the child’s parent. Sometimes DFPS is named PMC and parental rights aren’t terminated (such is in the example above). DFPS may not have PMC long in some cases, such as those where children are placed right off the bat with foster parents who want to adopt them. But in some cases, DFPS’ PMC status lasts for years, even up to when a child ages out of foster care at age 18 or 21.

Permanency Hearings after Final Trial. By statute, the court is required to review PMC cases after final trial at least once every six months. The harsh reality of two reviews a year is that DFPS, and even children’s attorneys, may allow children’s needs to go unmet as there is little legal accountability during these six-month intervals. This could look like a child not getting a driver’s license when she turns 16 (translation: not having the same opportunities as every other kid in her class); a young adult aging out of care without having his original birth certificate and Social Security card (translation: not being able to get a state ID or employment); or a child remaining in a placement that is more restrictive than her needs (translation: the child missing out on normal childhood activities).

Practice Tip: Creating a PMC caseload handled by one prosecutor can allow the county to maintain consistent legal oversight of these cases. This prosecutor can stay knowledgeable about the cases even though DFPS caseworkers may change and request review hearings with the court as needed to ensure DFPS, the child’s attorney and/or guardian ad litem, and other parties still involved in the case are held accountable in meeting the needs of the children living indefinitely in the foster care system.

Impact by criminal cases

When a parent endangers or abuses a child, a criminal investigation may occur in conjunction with the CPI investigation. We often see these joint investigations in cases where children go to the hospital for unexplained traumatic injuries, sexual abuse, endangerment reported by citizens to law enforcement, or even child death cases. We don’t typically see criminal investigations pending in cases where children are removed for neglect—for example, when parents are using meth and not meeting the needs of their starving, dirty, lice- and flea-infested children.

In cases that have criminal investigations pending from the facts of the removal, a DFPS prosecutor should be tracking the criminal investigation to see if and when charges are filed; if and when there is an arrest; whether the parent gets indicted; and how the criminal case is resolved. Remember the child protection prosecutor’s burden at the two main contests in the case? At the Adversary Hearing there must be sufficient evidence to satisfy a person of ordinary prudence and caution, and at the termination trial the trier of fact must find clear and convincing evidence. A detective’s testimony that probable cause existed to charge and arrest a parent and/or a certified copy of a filed indictment can be really helpful at the adversary hearing in meeting this burden. And later down the road, a guilty plea and judgment of conviction can support clear and convincing evidence that a parent engaged in conduct which endangered the physical or emotional well-being of the child.

Some of the toughest cases child protection prosecutors face are physical abuse cases where criminal charges are not filed, both parents are in the abuse timeline, and the investigation has halted because there isn’t enough evidence to eliminate one of the parents as the perpetrator. Often by the end of the child protection case, both parents have cooperated fully with their service plan tasks, yet they are both denying physical abuse occurred. Even when the parents have checked all the boxes on their service plans, DFPS may still see these cases as high risk for re-injury due to the lack of accountability by either parent, in combination with the significance of the injuries sustained, and often still seeks termination due to that risk. But it can be hard to secure termination when the only ground the prosecutor has is endangering conduct based on the one instance of abuse and there are no arrests, indictments, convictions, or admissions to show who the abuser was.

Conclusion

To the criminal prosecutors who have gotten this far, I want to say thank you for reading this article and taking the time to better understand what your colleagues are doing in the family courts. Go check out a contested adversary hearing or termination trial when you can. If you really enjoy the challenging nature of these cases, maybe even consider joining our ranks!

To the child protection prosecutors who have made it this far, here’s a reminder that in comparison to the number of criminal prosecutors across the state, we may be small in number, but the impact of our work on the lives of children is tremendous and long-lasting. I was reminded of this a few weeks ago when, by chance, I was able to observe the adoption of two boys from one of my prior cases. Theirs happened to be one of the hardest, longest, most contested cases I have handled. I had to wipe away my tears as these two young men high-fived the judge. What an amazing event to be a part of.

Endnotes

[1] Tex. Fam. Code §264.009(a).

[2] Tex. Fam. Code §264.009(e).

[3] Tex. Fam. Code §264.009(d).

[4] Tex. Fam. Code §264.009(f).

[5] “The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) protects children and vulnerable adults from abuse, neglect, and exploitation” through “five major programs” that include: Adult Protective Services; Child Protective Services; Child Protective Investigations; Prevention and Early Intervention; and Statewide Intake.” www.dfps.texas.gov/About_DFPS/ default.asp.

[6] The stats in this section were gathered from the DFPS Data Book, specifically the CPI section located at www.dfps.texas.gov/About_DFPS/ Data_Book/Child_Protective_Investigations.

[7] These numbers were gathered from various sources and are not guaranteed to be exact.

[8] Tex. Fam. Code §61.303.

[9] Tex. Fam. Code §264.203.

[10] Tex. Fam. Code §82.002(d)(2). DFPS may file for the protection of any person alleged to be a victim of family violence.

[11] Tex. Fam. Code §262.1015.

[12] Tex. Fam. Code §262.105.

[13] Tex. Fam. Code §262.101.

[14] Tex. Fam. Code §262.101(b), amended by Acts 2023, 88th Leg. R.S. Ch. 672 (HB 968) §1, eff. Sept. 1, 2023.

[15] Tex. Fam. Code §262.201(j)(1)(2).

[16] Tex. Fam. Code §262.2015.

[17] Tex. Fam. Code §263.101.

[18] Tex. Fam. Code §161.001(b)(1)(O).

[19] Tex. Fam. Code §262.2015.

[20] Tex. Fam. Code §262.304.

[21] Tex. Fam. Code §161.001.